(#157) Most read 8 insights in 2025

Dear Reader,

Below you can find the most read 8 insights in 2025:

A concise Masterplan for 🇪🇺 Europe’s rebirth

Aggregation wins again: How Netflix outbid Hollywood

TikTok Shop and the rise of content-native commerce

Microsoft 🤝 OpenAI: until AGI will do us apart

ChatGPT Atlas and the battle for the New Interface Layer

Apple’s boring decade

Tesla vs. Waymo

The Internet vs. S&P 493

Onto the update:

1) A concise Masterplan for 🇪🇺 Europe’s rebirth

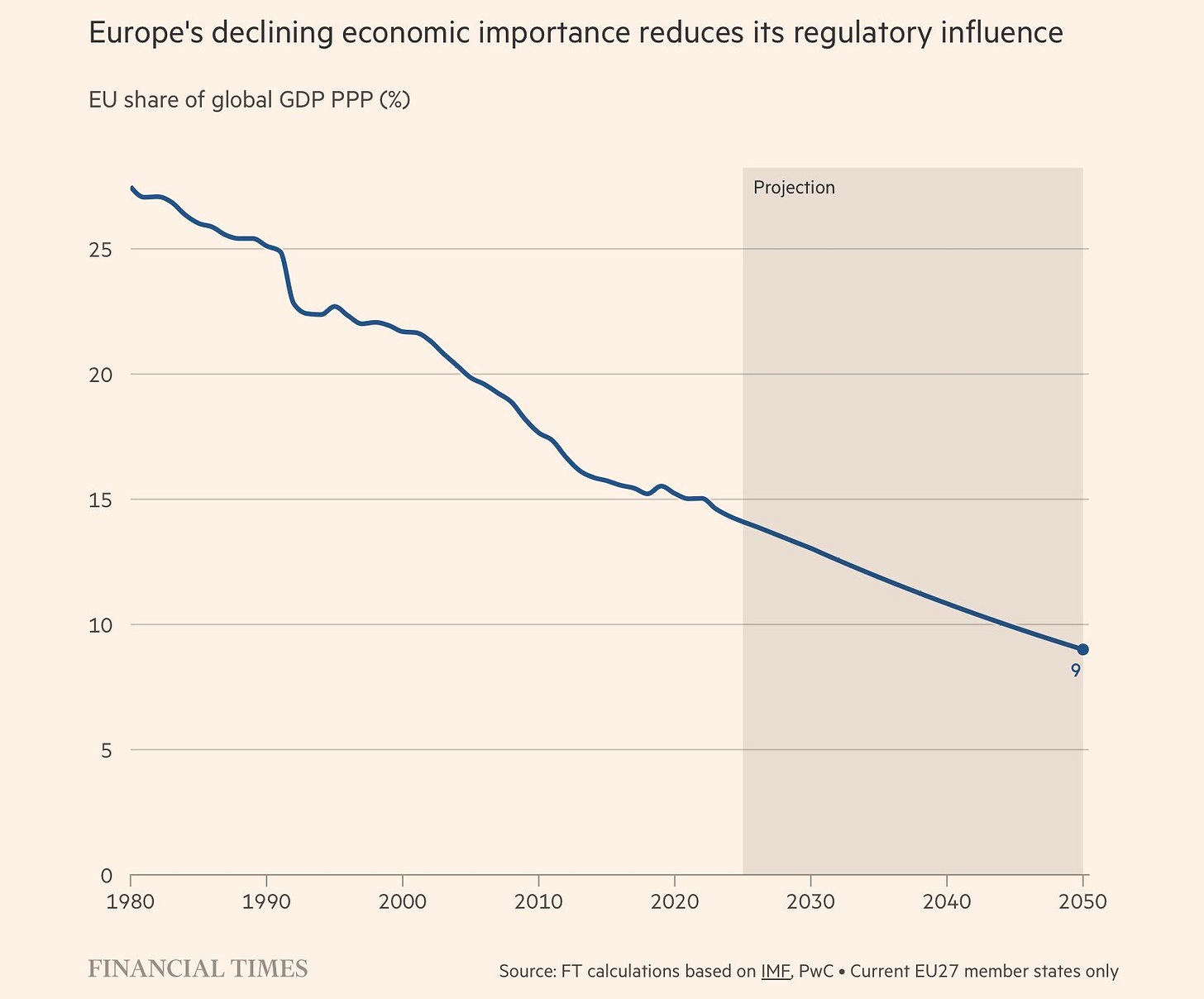

Europe loses because rules are downstream of economic gravity. When your share of global output slides for decades (and the chart is basically a ski slope into the projection zone), you stop being the default market everyone optimizes for, and your “Brussels effect” turns from leverage into paperwork.

Reversing that trend is not a seminar on “competitiveness”. It’s a decision to be a builder civilization again:

1/ ship abundant energy (nuclear + grids + storage + faster permitting),

2/ ship compute (data centers, chips, sovereign cloud that actually scales),

3/ ship AI (less fear-as-policy, more deployment-as-policy),

4/ ship housing (yes, housing is industrial policy and YES, no houses, no babies 👶), and

5/ ship infrastructure (ports, rail, digital, defense production)

....ALL THE ABOVE at wartime speed.

Then: make it stupid-easy to start and scale companies across the EU. For this you need one market, one set of rules, real Capital Markets Union, stock-based compensation, bankruptcy that doesn’t brand founders for life, procurement that buys from European startups instead of subsidized Chinese stuff, and a migration system that recruits the world’s top engineers like it’s the Champions League.

Europe has world-class research, and now it just needs world-class commercialization velocity.

Of course, that means confronting the core mismatch: Europe is trying to regulate its way back to relevance while other regions are engineering, financing, and manufacturing their way forward.

Build an innovation flywheel around three engines:

(1) productivity software everywhere (AI copilots in SMEs, public sector digitization, mandatory interoperability),

(2) reindustrialization, where Europe can dominate (advanced manufacturing, robotics, energy tech, biotech, space, defense), and

(3) scale capital (pensions + insurers as long-term risk capital, deeper public markets, fewer national silos).

If Europe wants to bend the curve, it must choose: be the continent that primarily consumes technology and arbitrates its risks or the continent that creates technology, compounds productivity, and therefore earns the power to set the rules.

The chart above is the bill for decades of under-building. Pay for it with construction, and things will reverse. Let’s build!

2) Aggregation wins again: How Netflix outbid Hollywood

Netflix didn’t win the Warner Bros. auction because it had the best content library, actually, Warner Bros already had that. Netflix won because it’s an internet company that understands scale, velocity, and aggregation. The legacy Hollywood players like Paramount and Comcast came to the table with old playbooks: bundle the cable assets, merge libraries, and call it synergy. Netflix, on the other hand, pitched distribution, global reach, tech infrastructure, and the ability to monetize Warner IP across 300+ million subscribers. In short, Warner Bros. had the content, but Netflix had the platform. The deal was about what Netflix could do with it.

This reinforces the core lesson of the Aggregation Theory and the Elimination Strategy: once you control demand, suppliers become interchangeable. Warner Bros. was once the upstream king; now it’s an input to a vertically integrated machine.

Netflix’s pitch was basically “we’ll extract more value from your assets than anyone else”. The traditional studio system that once dismissed Netflix as a disruptor is now being absorbed by it. Content is valuable, but being the operating system of attention is exponentially more powerful. (Bloomberg)

More about Netflix and its moat this Sunday on WhereIsMyMoat.com

3) TikTok Shop and the rise of content-native commerce

TikTok Shop is emerging as a new type of e-commerce platform. It has reached 15 billion dollars in annual sales in the United States, placing it alongside eBay on the global stage. Its growth comes from integrating product discovery directly into entertainment. Instead of relying on search or reviews, TikTok drives purchases through algorithmic recommendations, creator endorsements, and continuous engagement. People watch videos, follow creators, and encounter products in context. Shopping becomes a part of the content experience. This approach treats distribution as a core function of the platform rather than a separate commercial layer.

The strategy works especially well for unbranded products and spontaneous purchases. TikTok Shop does not require strong brand identity to achieve high conversion. It relies on price appeal, creator influence, and the speed of content-driven trends. Consumers are influenced by trust in creators and the immediacy of the feed. eBay focuses on intent and listings. TikTok focuses on discovery and engagement. The model represents a shift in how younger generations interact with commerce. Videos, creators, and short-form narratives guide purchase decisions. This is a framework for the next generation of marketplaces, shaped by attention and content flow rather than catalog and search. WaPo

4) Microsoft 🤝 OpenAI: until AGI will do us apart

1/ The new Microsoft - OpenAI agreement is a clear example of strategic modularity under constraints. What began as a highly integrated, almost captive-style partnership is evolving into something more balanced. Microsoft retains exclusivity over core APIs, access to key research IP (until AGI is verified), and a massive Azure workload. But OpenAI gains new degrees of freedom, which is, joint development with third parties, open weight model releases, and government contracts on any cloud. Both parties are now platform-scale players.

2/ The core insight is that both Microsoft and OpenAI are preparing for a post-foundational model world. Up to now, the play has been about building and commercializing the biggest, most capable models. But going forward, the differentiation will come from distribution (Microsoft), ecosystem integrations (Azure + Copilot), and fine-tuned, agentic workflows (OpenAI). That’s why Microsoft gets long-dated IP rights and product exclusivity (ie. it’s hedging against model commoditization while investing in where the real value will compound: applied usage across its productivity suite and developer platforms.)

3/ The OpenAI side of the deal is equally strategic. Recapitalizing as a public benefit corporation (PBC), with Microsoft holding 27% on a diluted basis, signals a shift in how the company wants to scale. That is, more independence, more optionality, and more enterprise-grade alignment. The fact that OpenAI can now serve national security clients on any cloud and release open-weight models is a recognition that the future isn’t just consumer AI, but infrastructure-level AI governance and access. This sets OpenAI up not just as a model lab, but as a quasi-public utility with geopolitical relevance.

4/ The most important new clause is about AGI. It’s no longer a self-declared milestone. It must now be verified by an independent panel. This may sound like a soft governance point, but strategically, it’s a way to de-risk OpenAI’s control over the trigger event that would rewrite the entire agreement. Until AGI is declared (and verified), Microsoft’s favorable terms (e.g. IP rights, revenue sharing, exclusivity) stay in place. This slows down the rate of disruption, which benefits Microsoft’s go-to-market machinery, while giving OpenAI the runway to scale globally without immediate legal or technical redefinition.

5/ Ultimately, this agreement is about locking in optionality while preserving leverage. Microsoft gets durable distribution control and operational clarity. OpenAI gets more freedom to partner, release, and evolve. And the entire market gets a signal: the platform war is about who controls the workflows, infrastructure, and economic capture in a world where intelligence becomes the interface. This deal outlines the new architecture of the AI economy. LINK

5) ChatGPT Atlas and the battle for the New Interface Layer

OpenAI’s launch of ChatGPT Atlas represents a clear shift in platform ambition: from model to interface. Up until now, ChatGPT has existed as a layer within someone else’s ecosystem (e.g. Apple, Microsoft, the browser). But with Atlas, OpenAI is trying to own the frame in which that intelligence is used. The browser is a strategic surface area where users spend time, where search starts, and where intent is converted into action. With “agent mode”, OpenAI is turning the browser into an operating system for intent, where the AI acts on your behalf.

The strategic implication here is that OpenAI is moving down the stack, building a native interface layer that can disintermediate both Google (search) and Apple (UI control). This is the exact strategy Apple used against Microsoft with the iphone, that is, not by replacing Windows, but by building a superior, more integrated experience on new hardware. OpenAI is betting that LLMs + interface + memory + agency = a new kind of platform, one where the user’s context is persistent, the actions are intelligent, and the competition is legacy UX. Whether it succeeds or not depends on how many people want their browser to think instead of just render. But if this works, this will evolve from a browser war to a desktop war. OpenAI is building the first AI-native OS. LINK

6) Apple’s boring decade

Apple’s fall event is still the Super Bowl of consumer tech, but now it feels more like watching a dynasty team run the ball up the middle. The iPhone 17 Pro is sturdier, with Ceramic Shield 2 and a unibody aluminum frame. The overheating problems of the titanium 15 Pro are fixed with a vapor chamber. Battery life is better. Cameras are sharper, with 48-megapixel sensors across the board and a Center Stage selfie camera that finally makes landscape selfies tolerable. It’s all good. It’s all incremental. And that’s the paradox: when you’ve already perfected the form factor (ie. a glass-and-metal slab that fits in your pocket) “new” mostly means “better.”

The iPhone Air is the exception, Apple’s big swing at reinvention. It’s thinner and lighter than anything before it, so thin you almost wonder if it breaks the first time you sit down with it in your pocket. But the compromises are obvious: weaker battery, fewer cameras, and a $99 battery attachment that is “optional” in the same way a charger is “optional”. It’s a marvel of engineering, but it’s also a proof of concept, a future you can look at but maybe shouldn’t buy yet. A triumph and a gimmick at the same time.

Meanwhile, Apple Watch and AirPods got modest but meaningful updates: hypertension detection that works across older models, satellite texting for hikers, and AirPods Pro 3 with heart-rate monitoring and a better fit. These are smart, thoughtful improvements that lock people deeper into the ecosystem. But they’re not going to make teenagers line up outside Apple stores or send X (tTwitter) into a frenzy. They’re utilities, not cultural moments.

And that’s really the shift. Apple is still a juggernaut, still running a business model that marries hardware and software better than anyone. The company is printing money from services, App Store fees, and Google’s $20 billion a year just to stay the iPhone’s default search engine. But the cost of those easy profits is visible. Apple didn’t invest in the messy stuff (data infrastructure, search, or AI) and now finds itself playing catch-up. When people talk about “the future”, they’re talking about Musk’s robotaxis, humanoid robots, or rockets, not Apple’s vapor chamber cooling system (!)

The irony is that Apple is still innovating internally. The iPhone Air’s engineering is extraordinary. The iPhone 17 Pro is probably the best smartphone ever made. But the vibe has changed. A decade ago, Apple events were the future. Now they’re the present, iterated. That’s not bad, but it’s arguably the most enviable corporate position on Earth. But it means Apple has slipped from being the company you follow to see what’s next, to the company you buy from because you know exactly what you’re getting, ie. the best version of the same thing you already own.

So yes, Apple is still changing the world. Just not in the way that captures imagination anymore. They’re the mature incumbent, selling a better kind of a utility, while the crazy moonshot stuff (EVs, robots, AI) is happening somewhere else. The danger is that Apple will lose relevance in the cultural imagination. And for a company built on making people want to be part of its story, that’s the real cost of incrementalism. LINK

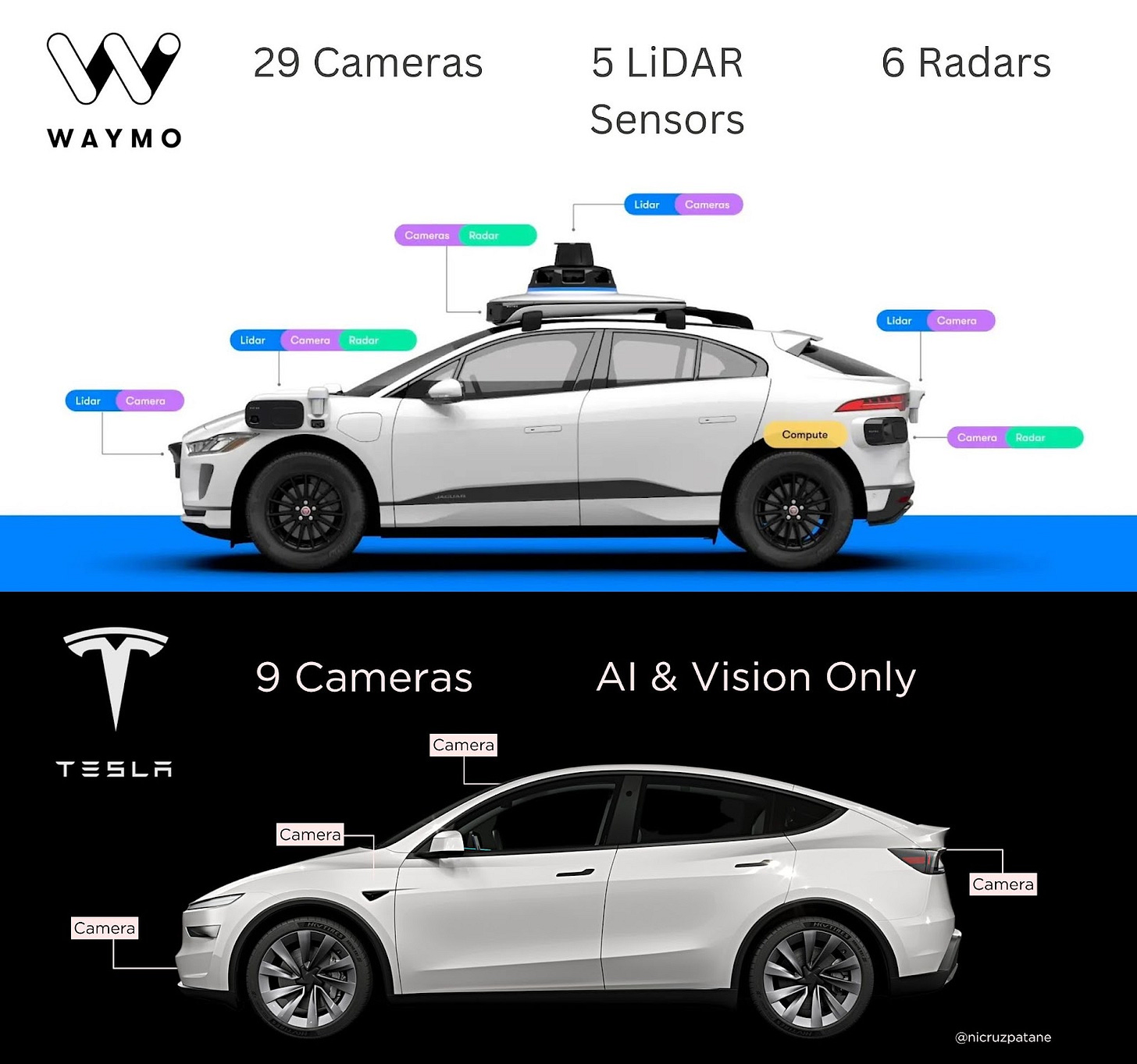

7) Tesla vs. Waymo

1/ Waymo’s car looks like it lost a fight with a RadioShack. It has 29 cameras, 5 LiDARs, and 6 radars stapled onto every available surface, like someone was trying to win a bet about how much hardware you could legally attach to a Jaguar. And it works, sort of. Waymo’s approach to autonomy is: map the world down to the last manhole cover, then drown the car in sensors so it never has to guess. The result is a robotaxi that performs pretty well in limited zones and costs so much to build that you wonder if it’s actually a tech product or just a proof of concept with a burn rate.

2/ Tesla, on the other hand, has a software problem. Its cars rely on nine cheap cameras and a whole lot of hope that machine learning will eventually see the world better than humans do. The bet is bold: vision-only, no maps, no LiDAR, just AI. And yes, that software isn’t quite there yet. But the thing about software problems is they scale well. Once solved, they can be patched over the air and instantly deployed to millions of cars. Hardware problems, on the other hand, need factories, supply chains, and years of retrofitting. So yes, Tesla’s autonomy may hallucinate a traffic cone or two, but at least it’s not trying to reinvent the roof rack industry along the way.

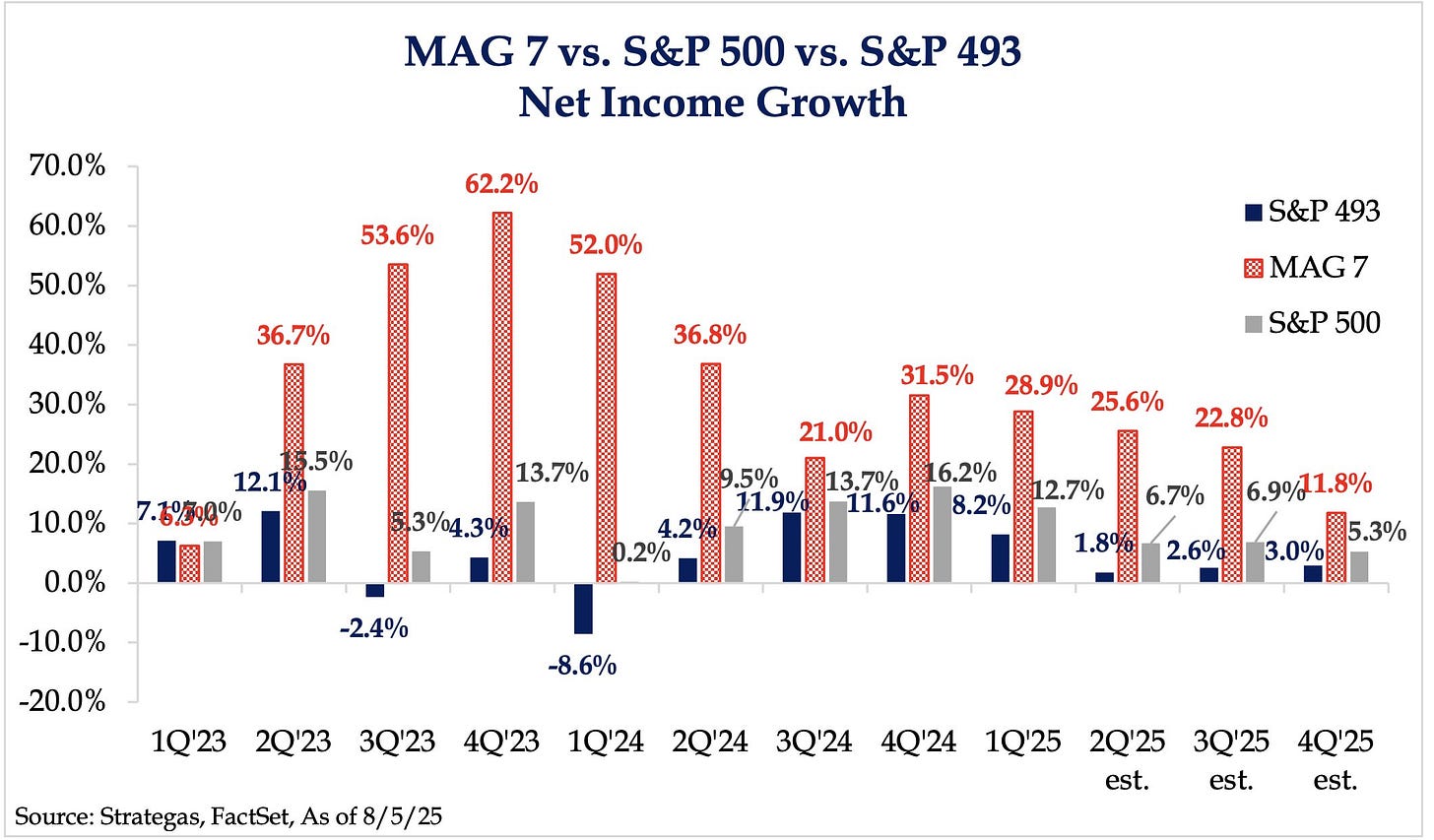

8) The Internet vs. S&P 493

What we’re looking at here is a three-way race: the S&P 500 (the market), the MAG 7 (Big Tech), and the S&P 493 (the rest of the economy pretending it’s still 2015). The MAG 7 is doing MAG 7 things, that is posting 50–60% net income growth like they are a startup. Meanwhile, the S&P 493 is limping along with 2–3% growth, which is just fast enough to get outrun by inflation and laughed at by Nvidia shareholders. If the S&P 500 were a group project, seven kids built a working rocket ship while the other 493 brought glue sticks and excuses.

Balaji’s point - “the Internet is not the same as America”- is showed here in bright red bars. The US economy is bifurcating: one part is writing AI models, dominating global cloud infrastructure, and optimizing ad auctions; the other part is asking the Fed if it can please have another quarter point. The stock market knows this, which is why it’s priced like the MAG 7 are the market, and everything else is beta ballast.

In conclusion, America, minus the internet, is kind of boring and probably overvalued. LINK

💡My 2025 annual presentation, “The Compresses Decade”, is now available to anyone on my blog: https://onstrategy.eu/presentation

WIMM - Where is my MOAT?

If you enjoy my strategy notes on LinkedIn or in OnStrategy, WhereIsMyMoat.com is the deeper, “skin-in-the-game” version: full theses, moat scoring, and a clear view of the company’s future performance.

Last week’s analysis:

🚜 Caterpillar’s quiet pivot to uptime

🛒 PayPal is moving from ‘Button’ to ‘Platform’

This week’s analysis:

Consider subscribing: